Do the slide show and video before reading the Introduction.

|

Larry's Intro Chs. 7-8: The Genius of Hell and Time's Arrow

Rowlands uses this dispiriting trajectory to do some rabbit hunting of the familiar philosophical topics love and friendship. Indeed philosophy means "love of wisdom," so it has been interested in love from the beginning: Our sense of loyalty to each other now outstripped our sense of justice to others. We had become a pack ... And those outside our nation didn't matter to us ... (142).

Just what can friendship mean with a friend not built to deceive or calculate? Rowland's heartbreak was that his attempt to save Brenin's life was impossible for Brenin to understand. For a wolf, friends never cause each other pain.

Illness and a Broken Heart Southern France seemed like an unparalleled opportunity--lots of time to write for Rowlands and lots of space to run for his three canines in tow. Mountains, sea, quaint villages, and wonderful food. But Brenin needed a vet, a good one: Brenin had a highly antibiotic resistant form of E. coli similar ... The upshot was that he was almost certainly going to die. (175) This tragedy raised the classical questions of love, friendship and suffering. Given the suffering inflicted on Brenin, Rowlands worried Brenin would conclude he was no longer loved: "this broke my heart and I think a little piece of it will always remain broken" (177).

Love is the Path to the Deepest Hell

(1) traditional view of Hell a place where those not saved would be tortured in pain. The weak rarely have contracts--they are exploited without them. (2) Rowland's view of Hell a place where a person must brutalize the one most loved.

Love Has Many Faces: The Harshness of Philia

(2) there are many kinds of feelings stemming from philia, depending on the context.

Wittgenstein: death is the limit of a life; it is not something that occurs in life.

Consciousness ends with death so there is neither pleasure nor pain. The fear of death arises from the belief that in death, there is awareness of death. Question: what is wrong with the argument? Option 1 : death harms because it steals possibilities. Rebuttal: too many possibilities (some good, many bad). We need the concepts of desire, goals and projects since all are future-oriented. A future is something we possess now. Option 2: it is only some of our possibilties that are important. Refinement: we hope these come true.

Conclusion: Death deprives us of the future we have now--states that bind us toward a desirable future.

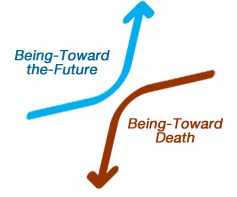

Heidegger: we are beings-toward-the-future, yet beings-toward-death. Time is a line (we have great ambivalence toward the line) Meaning originates in the arrow of desire, goals, projects. The line reminds us our arrows will be cut-off mid-flight.

"We can never enjoy the moment for what it is in itself [like a wolf] because for us the moment is never what it is in inself. The moment is endlessly deferred both forwards and backwards. What counts for us now is constituted by our memories of what has gone before and our expectations of things yet to come" (207) Moment of the present is deferred through time and is unreal in a way never true for a wolf. Apes plan and deceive, wolves relish the moment. Some insights: "Wolves and dogs pass Nietzsche's test in a way people rarely do" "People try to find happiness in the new and different so as to deviate from time's arrow" "The human search for happiness is regressive and futile" "At the end of every line is nevermore" "Time's arrow both fascinates and horrifies us" "Our understanding of time is our damnation" "Always, I have carried my death with me"

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Questions and Explorations Part 1

Philia. Philadelphia.

2. How does Rowlands redefine the traditional view of hell (which he despises) and why?The traditional view is that those who are hateful are not saved and go to everlasting hell. Given his experience with Brenin, he redefines Hell as where you go when you inflict suffering on the one you love in the vain attempt to save their life. Remember, Rowlands wanted to believe that those who love will never go to Hell. He reached the conclusion that those who genuinely love are the best candidates for Hell.

3. How does Rowlands deepen Aristotle's definition of philia?Philia is "brotherly love," just as Aristotle wrote, but it can be more demanding than Aristotle understood. It involves the willingness to love to the point of inflicting suffering, in the hope the suffering is the route to recovering from illness.

4.

|

|

"I've Loved You So Long" (6 min.)

|

|---|

Rowlands suffered vicariously through Brenin while Nietzsche suffered more directly. But both recognized that suffering is inevitably, perhaps essentially, a part of seeing the meaning in life.

Watts saw death as an inevitable part of the experience of life and to resist it is to resist the natural order of things. Rowlands, though British, is more typically American in viewing death as an enemy to be avoided.

Watts comments at the outset that "there isn't really anything radically wrong with getting sick or dying." Given the pain that he saw Brenin go through, Rowlands would disagree. Watts welcomes the natural order of things, Rowlands sometimes needs a fifth of whiskey to cope.

View the film clip at right and answer the two questions. Set-up: why Juliette was in prison is revealed slowly: that she was in prison for 15 years, that her crime was murder, that the victim was her 6-year-old son, and last the reason why she killed him.

5. What concepts does Rowlands add that accounts for our future-oriented awareness such that the future is something we can lose at death? How does this challenge the traditional view of Epicurus?

We need the concepts of desire, goals and projects since all are future-oriented. Since future is something we possess now, that is what we lose at the moment of death.

We need the concepts of desire, goals and projects since all are future-oriented. Since future is something we possess now, that is what we lose at the moment of death.

Brenin lost less since he had very limited desires and goals and presumably no projects. Not "damned" by time's arrow, Brenin was free to live each moment in a circular way. Brenin the Reaper at right looks very cool, maybe even should appear in a werewolf movie, but in life he paid the Grim Reaper little mind.

Epicurus claimed "death is nothing to us." Rowlands argues that the ancient philosopher gets it wrong because it does mean something to us just because each moment is the link betwen past and future, with its desires, goals and projects.

6. Challenge: Given these concepts, how does Rowlands think he has an explanation for what you lose when you die?

Since the future with our desires, goals and projects are defined in terms we can have now, there is something that is lost at the moment of death by the person who dies. The future can be present in a powerful way for a person that it cannot be for a wolf.

Since the future with our desires, goals and projects are defined in terms we can have now, there is something that is lost at the moment of death by the person who dies. The future can be present in a powerful way for a person that it cannot be for a wolf.

If you die this afternoon, you lose your desired goal of writing the world's best philosophy paper for PHI 110!

Part 2

So it should not be suprising that he thinks of the pursuit of basic pleasure to be associated with ages 18-30. That does not mean you should fall in the same trap. He was lucky to get another job after Alabama. 1. Challenge: why is it not surprising that Kant thought in terms of spatial metaphors which thinking about time?

Time seems to have three dimensions, of course, past, present and future, and we seem to move through them as an airplane moves through the sky. He thought in terms of the flight of the arrow.

Time seems to have three dimensions, of course, past, present and future, and we seem to move through them as an airplane moves through the sky. He thought in terms of the flight of the arrow.

2. What is the contradiction did Heidegger identify that seems to drive us, in terms of time and death?

Heidegger illuminates in a new way the taking-as structure that he takes to be the essence of human existence. People areessentially finite. This finitude explains why the phenomenon of taking-as is an essential characteristic of our existence.

Heidegger illuminates in a new way the taking-as structure that he takes to be the essence of human existence. People areessentially finite. This finitude explains why the phenomenon of taking-as is an essential characteristic of our existence.

We are caught between the contradiction of being-toward-the-future, on one hand, and being-toward-death on the other. The only way to get closer to the future we want is to get closer to the death we dread.

3.  Exploration: What is Rowlands doing in this important chapter that illustrates "chasing rabbits" philosophically? Why is such an ability important to your future?

Exploration: What is Rowlands doing in this important chapter that illustrates "chasing rabbits" philosophically? Why is such an ability important to your future?

|

"Why is Philosophy Like Rabbit Hunting?" (10 min.)

|

|---|

Rowlands is trying to do better than those who went before in making sense of his own experience, what would drive him to drinking large volumes of whiskey and dreaming about recently departed, beloved wolves.

Chasing rabbits metaphorically is what will keep you employed in the future in a world saturated by both turbulence and artificial intelligence. You need to be able to hunt rabbits--so to speak--if you are going to feed yourself.

Please do the video in the sidebar at right and answer those questions.

4. People deceive, wolves do not, but what is the difference between people and wolves in terms of how they view time?

The wolf lives each moment in the moment, not exercised by plans for tomorrow or regrets about yesterday. The wolf's view is circular rather than linear.

The wolf lives each moment in the moment, not exercised by plans for tomorrow or regrets about yesterday. The wolf's view is circular rather than linear.

Rowlands observes that we are never finally in the moment because each moment is "endlessly deferred in terms of both the past and the future." Apes plan, deceive, calculate, stranded in the present between the past and the future. Wolves relish the moment, each moment, reminding apes of what it is simply to relish being alive in the moment.

Apes chase the rabbits of forgiveness for the past and the things that might be.

5. Challenge: Why would Rowlands make the puzzling comment, "Our understanding of time is our damnation"? What is so damning about time's arrow?

We fret about time's arrows as each moment passes, mindful that our time is limited and that the time of all those we love is limited. We are far more exercised about time and the future than other non-human animals such as wolves.

We fret about time's arrows as each moment passes, mindful that our time is limited and that the time of all those we love is limited. We are far more exercised about time and the future than other non-human animals such as wolves.

As he puts it, we carry our deaths within us, mindful of the diminishing days.

Preoccupation with death can eviscerate the moment so we cannot enjoy hunting rabbits, metaphorically speaking.

6. Nietzsche is puzzling, outrageous, not respected in some philosophy circles, yet he is one of the most widely read philosophers. How come?

Nietzsche famously wrote of "the death of God" and strove to dethrone traditional ways of thinking about what it means to be human, both philosophically and religiously. Some interpreters of Nietzsche believe he simply rejected philosophical reasoning, replacing it wth a literary exploration of the human condition that was fundamentally pessimistic and unhelpful.

Nietzsche famously wrote of "the death of God" and strove to dethrone traditional ways of thinking about what it means to be human, both philosophically and religiously. Some interpreters of Nietzsche believe he simply rejected philosophical reasoning, replacing it wth a literary exploration of the human condition that was fundamentally pessimistic and unhelpful.

Other interpreters say he was engaged in a positive program to affirm life, and so he called for a radical, naturalist rethinking of what it means to be human.

On either interpretation, it is widely agreed that he represents a major challenge to conventional, modern thinking, one that was welcomed, at various times, by a wide range of writers, from Nazis to New-Age leftists, each claiming his radical challenge for their own projects.

|

Notes |

|---|

Fixing a Broken Heart (12 min., first 6). Counselor Guy Winch tells us that "hope can be incredibly destructive when your heart is broken." What evidence is there of this in Rowland's account of Brenin's illness?

Fixing a Broken Heart (12 min., first 6). Counselor Guy Winch tells us that "hope can be incredibly destructive when your heart is broken." What evidence is there of this in Rowland's account of Brenin's illness?

When Rowlands writes "This broke my heart, and I think a little piece of it will always remain broken," he sounds like he could use Guy Winch's counseling.

When Rowlands writes "This broke my heart, and I think a little piece of it will always remain broken," he sounds like he could use Guy Winch's counseling.

The classical vision is that the hateful people go to Hell, and the loving to the good place. He found that his outsized love for Brenin took him to a worst Hell of imagining that Brenin concluded Rowlands no longer loved him.

The classical vision is that the hateful people go to Hell, and the loving to the good place. He found that his outsized love for Brenin took him to a worst Hell of imagining that Brenin concluded Rowlands no longer loved him.  (1) feelings can result from

(1) feelings can result from

Epicurus: "death is nothing to us. When we exist, death is not; and when death exists, we are not."

Epicurus: "death is nothing to us. When we exist, death is not; and when death exists, we are not."  Kant: time's metaphors are all

Kant: time's metaphors are all

Nietzsche was ill much of his life, with debilitating pain. After he moved to Sils Maria in Switzerland, he framed his famous notion of the

Nietzsche was ill much of his life, with debilitating pain. After he moved to Sils Maria in Switzerland, he framed his famous notion of the