Do the slide show and video before reading the Introduction.

Little Red Riding Hood (3 min) goes back eons in folklore and mythic history and keeps being re-incarnated. Little Red Riding Hood (3 min) goes back eons in folklore and mythic history and keeps being re-incarnated.

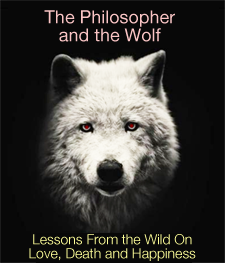

Whatever the reason, fear of the wolf is a deep part of human culture and human psychology. This is part of the reason for the appeal of Rowland's book.

|

Mark Rowlands interweaves classical philosophical questions with anecdotes of raising his pet wolf, Brenin. Rowlands brings philosophical training (Ph.D., Oxford) to his life engaging wolves more than people, setting the stage for Rowland's atttempt to learn what the wolf has to teach us. Rowlands and his well-traveled wolf spent more than a decade as daily companions with Brenin spending more time in classrooms than any wolf in history: He ... was the beneficiary of more free university education than any wolf that ever lived ... when the lectures became particularly tedious, he would sit up and howl--a habit that endeared him to the students ... wishing they could do the same. (p. 1). More than just an exotic pet, Brenin was for Rowlands a canine person, and their life and death struggles lead him to re-evaluate his attitude to what it means to be human, what happiness is, and how death conditions our view of life.

The Wolf in Literature and Film The Big Bad Wolf is a fictional wolf appearing in several tales, including Aesop's Fables (c. 600 BC) and Grimm's Fairy Tales. Versions of this character have appeared in numerous works, and it long been a mythical figure in fiction and folklore. Little Red Riding Hood as well as The Three Little Pigs reflect the theme of the threat the wolf represents to the vulnerable and innocent. The conversation between the mythical wolf and Little Red Riding Hood has its analogies to the Norse myths of old and is reflected all the up to modern pop with Sam the Sham and the Pharoah's, "Little Red Riding Hood." Cultural anthropologists see the wolf representing the night swallowing the sun, and the variations in which Little Red Riding Hood is cut out of the wolf's belly represent the dawn. In fact, wolves were dangerous predators and such fables served as warnings not to enter forests where wolves lived. Both wolves and wilderness were treated as enemies of humanity in that region and time.

The story of Little Red Riding Hood dates back centuries in different countries with some versions 3,000 years old. In France it was a more sinister tale of a young girl who goes to visit her grandmother and meets a werewolf:

A similar story from China is called The Grandmother Tiger. There are also variations of the story from the Middle East and Africa. In one version of the story, the wolf gives the girl some food to eat which is part of the body of her grandmother. The Brothers Grimm and other later authors added male heroes who save Red Riding Hood. The Wolf Pack and Ape Deceit: What Philosophy DoesRowlands was raised around large dogs but also describes his family of origin as "dysfunctional." As a result, he had a command of raising canines such as dogs and wolves but also was disposed to pursue what it means to be human, given that we can get things so "balls-up," as the British would say. Humans are inclined to deception and, worst of all, self-deception. There's an entire school of philosophy, existentialism, that emphasizes our ability to deceive ourselves, on the assumption it is the only way we can live with ourselves. The book is a compelling story about a loner and sometime drunkard who takes "the stories we tell ourselves" seriously but is not content to accept standard, cultural explanations. Neither is he inclined to accept standard religious explanations about who and what we are, and he resists standard analytic philosophy about how mind should be understood (i.e., it is "reducible to brain since all that is real is matter").

Challenging Conventional Wisdom Philosophy challenges conventional understanding when it is built on indefensible assumptions ("wolves are vicious", "party x is immoral," "people who look like that are sub-human"). Fear of wolves is shaped by folklore designed to scare children into frenzied delight, but misrepresent the way the world works. In order to challenge conventional understanding, Rowlands suggests we need to consider what (uncritical) assumptions underlie such understanding. If it can be shown to be indefensible, then it can be exposed as indefensible and becomes a belief we should drop. You probably don't worry about roaming demons trying to get you, or vampires flying into your room at night to drain your blood, or sorcerers stirring a bowel of evil magic designed to do you harm. We no longer believe that rocks are completely hard (science has shown that), or that certain people are inferior to others (whether by ethnic or sexual identification or by religious affiliation). It was obvious to our ancestors that people come in exactly two genders, a belief that many of us see as both factually untrue and ethically unjust. Fear of Wolves and Philosophy: The Clearing SpaceSo what is Roland's philosophical goal? To get us to see that our fear of wolves (as well as many other fears) is one more prejudice born of misinformation and fear, passed on down through the generations, and magnified by folklore and popular culture (see Don Henley's masterful lyrics "New York Minute" at right, covered by Michael Omartian, about 2:20). Philosophy is the oldest academic activity, dating to Plato in Greece, Bantu philosophy in sub-Saharan Africa, and Confucious in China. Philosophy continued to be the backbone of academic research until specific disciplines emerged in the 19th century. Socrates, you might know, was executed for challenging traditional beliefs thought necessary for social cohesion, as well as corrupting the youth of his day.

But coming to see wolves in another light is an example, not the only end. Philosophy generally is the activity of examing assumptions that undergird strongly held beliefs that may be counterproductive socially or in the natural world. It's hard work (Rowlands compares it to Brenin's hunting of rabbits in thick brush). Especially in contentious times, we need a clearing space where ideas can be exchanged productively; we need philosophy more than ever. Rowlands concludes the first chapter by observing that "These are the thoughts of the clearing ... that exist in the space between a wolf and a man." | ||||||

|

Questions and Explorations Part 1

Experience with his wolf convinced Rowlands that we are more like apes than wolves, with the capacity to deceive.

| |

|

"Inside the Minds of Animals" (5 min.) |

|

|---|---|

|

Rowlands is a professional philosopher who takes exception to much of what is claimed about animals, especially by Descartes, since he has lived in such close quarters with large dogs and of course Brenin for much of his life. He sees them as persons (of a somewhat different kind) that have rights since they are persons. But they are not machines. They feel, think, solve problems, love, fear, fight, and eventually die--like us.

Please do the video in the sidebar at right and answer those questions.

4. How does Brenin's "unprecedented life" (36) reinforce Rowlands' claim that wolves have more of a mind and was even able to learn language, something that would have astonished Descartes and many other writers? How is the human world a "magical world" (36)?

By living in a human world he had to learn human language--at least enough of it to live productively with Rowlands. Hence the extended discussion of the training he received.

By living in a human world he had to learn human language--at least enough of it to live productively with Rowlands. Hence the extended discussion of the training he received.

That we live in a "magical world" is Rowlands' way of talking about what it must be like to be domestic dog, with so many things beyond comprehension. Brenin entered that magical world, leaving the "mechanical world" behind. We too live in a magical world since the overwhelming number of things we live with (internet, quantum mechanics, politics, economics) is well beyond our understanding.

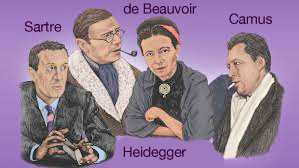

5. Challenge: How does Rowlands use his philosophy to respond to the challenge that it was unjust to keep Brenin as a pet wolf (37-38)? Does his argument work? And who is Sartre?

He calls it a "trick" in philosophy but is a basic academic skill you should employ. When people make claims (philosophical, religious, political), attempt to identify the assumptions ingredient in the claim that have not be spellled out and assessed. If you can identify such assumptions, then assess whether they are obviously the case or open to challenge. This is "doing philosophy."

The claim he confronted was that "wolves can only be happy engaging in natural behaviours such as hunting and interacting with their pack." Rowlands claims that the assumptions ingredient in such a view are not only not obviously true, they stem from "human arrogance."

He invokes the infamous Jean-Paul Sartre (the one with the pipe), the French existentialist who argued that existence precedes essence for humans, because we are "condemned to be free," while it is the reverse for animals, who are not free.

He invokes the infamous Jean-Paul Sartre (the one with the pipe), the French existentialist who argued that existence precedes essence for humans, because we are "condemned to be free," while it is the reverse for animals, who are not free.

Rowlands rejects an absolute distinction between the freedom of people and the bondage of animals, as you would expect. He would agree we probably have more freedom than animals but it is a relative distinction, not absolute. Your cat's haughty indifference, it might be disturbing to know, is partly freely chosen.

We will meet Sartre and the other existentialists later in the term.

6. Why do we read "Much of what I know about life and its meaning I learned from him. What it is to be human: I learned this from a wolf" (43)? Why does he write this, how does it exemplify philosophy, and is this language the Oxford Ph.D. speak or the Jack Daniels?

Philosophy examines the most basic questions and, as we just saw, attempts to identify the assumptions ingredient in claims that warrant a good philosophical look. Philosophy does not attempt to justify the status quo or the tradition or what parents, teachers and so on have taught you. Remember how Socrates challenged the status quo and had to drink the hemlock as a result. Philosophy critically examines claims made by ordinary people, politicians, and the most distinguished political scientists and physicists. Everything is on the table, including, unfortunately, the Jack Daniels.

Philosophy examines the most basic questions and, as we just saw, attempts to identify the assumptions ingredient in claims that warrant a good philosophical look. Philosophy does not attempt to justify the status quo or the tradition or what parents, teachers and so on have taught you. Remember how Socrates challenged the status quo and had to drink the hemlock as a result. Philosophy critically examines claims made by ordinary people, politicians, and the most distinguished political scientists and physicists. Everything is on the table, including, unfortunately, the Jack Daniels.

We shouldn't be surprised that he takes from his experience with Brenin the idea that Brenin taught him what it is to be human. The contrast of Brenin, sometimes mischievous, but never deceitful, brought into high relief our simian past (hop on the table, scratch both armpits at the same time, make sounds like a chimp then jump up and down) and its "smiling faces."

Just wait 'til next chapter.

|

Notes |

|---|

The wolf is a large, predatory animal, yet wolves do not attack humans, possibly because we walk on two legs. Perhaps the howling (think Wolf-Man Jack) or the fear of pack animals appeals to us.

The wolf is a large, predatory animal, yet wolves do not attack humans, possibly because we walk on two legs. Perhaps the howling (think Wolf-Man Jack) or the fear of pack animals appeals to us. Larry's Intro Chs. 1-2

Larry's Intro Chs. 1-2

The popular animated Shrek film series reversed many conventional roles found in fairy tales. Notably, that included depicting the Big Bad Wolf from Little Red Riding Hood as still wearing her grandmother's clothes and on much better terms with the three pigs.

The popular animated Shrek film series reversed many conventional roles found in fairy tales. Notably, that included depicting the Big Bad Wolf from Little Red Riding Hood as still wearing her grandmother's clothes and on much better terms with the three pigs. Primates pay attention to which way other primates are looking, trying to anticipate what they are up to. White parts in human eyes helps us to determine which way another human is looking--a legacy of the primate proclivity for

Primates pay attention to which way other primates are looking, trying to anticipate what they are up to. White parts in human eyes helps us to determine which way another human is looking--a legacy of the primate proclivity for  So the wolf is the

So the wolf is the

The "clearing space" allows "trees to emerge from the darkness into the light" (11). Rowlands hopes to move us from the darkness of many centuries of viewing wolves as "big bad wolves," of werewolves, of vicious animals who travel in packs, ferociously devouring the innocent and threatening human livelihoods, to a more enlightened view of an animal, unfortunately, much less vicious than we often are.

The "clearing space" allows "trees to emerge from the darkness into the light" (11). Rowlands hopes to move us from the darkness of many centuries of viewing wolves as "big bad wolves," of werewolves, of vicious animals who travel in packs, ferociously devouring the innocent and threatening human livelihoods, to a more enlightened view of an animal, unfortunately, much less vicious than we often are. As we will see, the human brain has a lot in common (not everything) with the ape brain. Primates, according to some theorists, advanced intellectually, stimulating by the advantages conferred by

As we will see, the human brain has a lot in common (not everything) with the ape brain. Primates, according to some theorists, advanced intellectually, stimulating by the advantages conferred by  Exploration

Exploration (1) animals can make sounds and communicate in a rudimentary way ("watch out!") but cannot express thoughts. Even "madmen" can communicate thoughts using language. It is not a matter of lack of organs of speech since parrots can mimic words. Saying words is not expressing a language.

(1) animals can make sounds and communicate in a rudimentary way ("watch out!") but cannot express thoughts. Even "madmen" can communicate thoughts using language. It is not a matter of lack of organs of speech since parrots can mimic words. Saying words is not expressing a language. At the end of chapter 1, he is reflecting on the fact that Brenin is no more, but that Brenin provided a clearing for self-understanding that metaphorically is like a clearing in the woods that otherwise block the light of the sun. The darkened woods is like the deceitful complexities of our lives that we often do not see, or do not choose to see.

At the end of chapter 1, he is reflecting on the fact that Brenin is no more, but that Brenin provided a clearing for self-understanding that metaphorically is like a clearing in the woods that otherwise block the light of the sun. The darkened woods is like the deceitful complexities of our lives that we often do not see, or do not choose to see.